Well it’s been a solid eight months since I’ve updated this thing. In those eight months, I’ve graduated and moved to South Korea, where I’m now working as a Native English Teacher at the top high school in my province.

Korean High Schools are no joke.

But I didn’t log in to post about that.

Actually, I logged in to posit a theory to y’all.

It’s about whether or not Jamaican Patois is a dialect or a separate language.

I did a couple final projects on the phonology and syntax of Jamaican Patois, and before now, I’d kind of thought Patois (and creoles in general, I guess), could be counted as their own distinct language categories, as opposed to simply dialects of an umbrella language (for example, Patois being a dialect of English).

Today, however, I am reconsidering this theory.

For many of my friends and I, Korean is not our second language. It is our third, or maybe even our fourth. One conversation we seem to have over and over regarding our Korean language acquisition is the conversation of transfer: how our L2s pop up to fill in the blank spaces of our L3s.

And how it’s never English that pops up to fill in those blank spaces.

I think it’s really significant that for us, it’s always the L2 that pops up to fill in those blank spaces and never English.

When I was studying for my M.A., I did just a teensie amount of research about L2-L3 transfer and whether or not it really exists. I would have to read about it a LOT more before I could actually comment on it intelligently, but I guess I did enough reading to have the vocabulary to posit this theory:

If Jamaican Patois is a separate language, then howcome I’m not experiencing any Patois transfer?

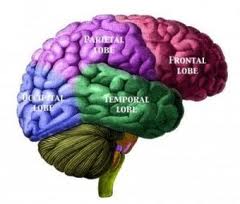

There are some scholars who think that the L2 and L1 are stored in different (yet overlapping) parts of the brain. This has been supported by Brocia’s apasia, which affects the L1, and Wernike’s aphasia, which affects the L2, and apparently a number of studies (which, admittedly, I have not read). According to a paper on the brain and language by Sumit Mundhra (2005), in the brains of late bilinguals (those who acquired their second langauge after the Critical Period), the “grammar and motor maps” of the L1 develop in close proximity, whereas they developed in a separate area for the L2. Additionally, data shows an “increased right hemisphere involvement for later-learned L2s in a single language environment” and a “left hemisphere localization of the L2.” Although Mundhra ultimately concluded that organization of the languages in the brain depends highly on the environment in which the language was learned, Wuilleman and Richards (1994) and Vaid (1993) concluded that age of acquisition influences brain organization as well, saying that languages acquired after the Critical Period involve more right brain than those acquired before.

The information in the paragraph above suggests and supports the theory that additional nonnative languages acquired after the critical period are stored differently in the brain than native languages. I think this explains why it is always L2s (for me and my friends) that pop up to fill in our blank spaces in Korean.

I started learning Spanish fairly young–you know, they teach you the days of the week and stuff when you’re in elementary school, and then I made Spanish my language concentration in middle and high school. When I was 18, I started learning some Jamaican Patois (mainly because I had a Jamaican boyfriend and wanted to understand him). In both languages, I got to the point where I could understand (most of ) conversations in real-time and understand the music of both languages, and to where I could express myself in both languages (although I’ve never needed to express myself in Jamaican Patois because everyone I know who speaks it code switches into English pretty much flawlessly).

However, by these events, and I admit I am using my own specific example in this case and would need to have a much less exclusive data sample to say anything conclusively; however, by these events, if Jamaican Patois is a separate language and not a dialect of English, then wouldn’t I be experiencing transfer from Patois as well, in the very least?

Then again, a paper by Ingrid Hendrick (2006) for the Teacher’s College, Columbia University, Hendrick writes that nonnative transfer can be dependent on the recency (which I did not know was a word) of language use and exposure, and in that case, I definitely have used/been exposed to far more Spanish than Patois in my life. Additionally, Hendrick writes that in the case of transfer, language learners most often borrow from the lexicons (vocabulary memory bank) of their nonnative languages, and there too, I have a much wider lexicon of words in Spanish than words in Patois (that are not also shared in English). Finally, Hendrick says that data suggests that language learners often experience nonnative language transfer when they are speaking, but they don’t want to use/sound like they’re using their native language. For my extent of knowledge of Patois, if I were to pull from my knowledge of it to fill in my Korean, I would basically sound like I was speaking Konglish, unless I wanted to adopt the phonology of Jamaican Patois, which would render me unintelligible to Koreans and is generally pretty rare as something that is transferred between nonnative languages.

So in conclusion….there is no conclusion. On the surface, the lack of transfer I’m experiencing could be used to suggest that Patois and English are organized in the same places in my brain, which could in turn suggest that Patois is a dialect of English and not a separate language. However, when explored beyond the surface even a little, there are several things that could explain the lack of transfer without challenging Patois’ language status. Therefore, at this point, the only thing that I can conclude is that I would need to study several folks who are not me but who are speakers of creoles to see if I can find anything more conclusive.